Vault

A Conversation with Poet Kathleen Peirce

Professor Kathleen Peirce discusses her latest book, Vault: A Poem, the poetic process, and the poetry community at Texas State.

Kathleen Peirce has been teaching poetry at Texas State University’s MFA since 1993. A graduate from Iowa Writer’s Workshop, she has published Mercy (Pitt Poetry Series) [1991]; Divided Touch, Divided Color [1995];The Oval Hour [1999-Iowa Poetry Prize winner]; The Ardors [2004]; and Vault: A Poem [2017]. She has won multiple awards, including the Guggenheim Fellowship in 2007, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in 2006, and the Iowa Poetry Prize. As a professor at Texas State, she has offered “Crossing In”, a class focused on the boundaries of voice in community by reading and practicing persona poems, reading translation theory, practicing translation, working as a volunteer to bring poetry to local communities outside of the university.

Last month [October, 2017] New Michigan Press released your latest book, Vault: A Poem. Vault is one poem told in 85 parts. What was the inspiration and reasoning behind that choice?

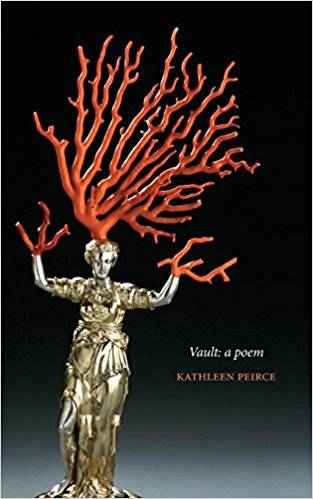

Initially, I was inspired by the small sculpture of Daphne that’s depicted on the book’s cover. I saw it in a Dresden museum of wondeworks, objects meticulously constructed for beauty’s sake alone. It stopped time for me, looking at it. My reasoning for the construction of a single long poem came about because it was the truest and most challenging form I could think of in relation to that sculpture and the myth it revisits.

What was the process of constructing this poem like?

It was like building a city in my head, for years, where I was the only one moving. I knew the poem would be collage-like, meditative, cumulative, though I didn’t project outcomes. I had to learn to trust materials from wildly different sources as they came into view, in the order that they came, and I agreed to follow their juxtapositions toward ends I needed to believe, in order to keep building and moving through.

Poet Ilya Kaminsky noted that in this book that, “[Peirce’s] poetics is aware that an encounter with a piece of art, (and, perhaps, language, too) is like entering a soul itself.” Would you agree with that? And if so, how would you describe the balance of artistic response—of both disappearing into a soul not your own and creating a soul for others to move inside of?

I’m very grateful for the gift Ilya made in those sentences! As for soul, I would say that I’m as interested in coming as close as I can to Aretha’s version as I am to the Pope’s. Or Joseph Cornell’s, Jean Valentine’s, Giorgio Agamben’s. If we agree to define soul as a received and made place, held briefly by bodies, known in instances, to contain without measure what we endure, they’re the same anyway. The feeling of being changed by art does seem to happen at a depth I’m not too shy to call soul-depth, and I relish it when it happens to me. Can I say I set out to create a soul for others to move inside of? I cannot. At best, that’s a silent high hope.

How has your poetics influenced your teaching? How has your teaching influenced your poetics?

My poetics lean on Fanny Howe’s value of bewilderment “...as a way of entering the day as much as the work. Bewilderment as a poetics and an ethics.”. That’s from the beginning of her fine essay, “Bewilderment”. This way of entering the day, the work, the classroom is a path toward learning to value possibility over certainty. It took me a long time to get there, to really be excitable, informed, vulnerable, curious, more alive in the means than the end. As a student at Iowa, my biggest lesson was to risk letting go of writing the kind of poem I was too easily being applauded for. My teachers could see that I was writing with the end of the poem always in front of me. They encouraged me to take bigger risks, to learn the value of having a stake in the process, and they stood by me. In my workshops at Texas State, everyone works toward taking similar risks as a reader. We work on becoming open as readers. We don’t fix each other’s poems; we each speak about the effects of the writer’s choices as we each interpret them. This practice is the callisthenic for coming to the blank page with greater possibility. It offers a celebration of options, and a chance for real surprises for the writer and the reader. Teaching workshop this way, and turning, returning to ideas in 5395 [Problems in Language and Literature courses] and Form and Theory profoundly support my reading and writing life outside of class.

“The Texas State poetry community is large, very strong, very much alive, and growing all the time. We’re at our best when our lives and ideas are diverse, when we’re vocal, and listening, and connected.”

How would you describe your Texas State poetry community?

My Texas State poetry community is only partly made up of current students, some of whom were not yet born when I taught my first graduate class here in 1993. I hold a lot of people in my heart! I’ve had the honor of teaching some who have published in top journals, won national awards, published books, started small presses, found teaching jobs at colleges in America and overseas. I feel the same honor to have taught students whose hard work has not yet been recognized, who keep writing, keep sending it out. And I feel the same honor to have taught students who are equally talented, who have stopped writing for some or many reasons but value their own minds more for having studied with us. The Texas State poetry community is large, very strong, very much alive, and growing all the time. We’re at our best when our lives and ideas are diverse, when we’re vocal, and listening, and connected. My colleagues on faculty are formidably talented, celebrated, dedicated poets and teachers. We’ve always been supportive of each other and our students.